I am far from the first to lament the recent loss, within a couple of days, of both Nicolas Roeg and Bernardo Bertolucci, and I certainly won’t be the last. What follows is not some sort of double obituary, but merely a brief, personal appreciation of two major filmmakers, both of whom proved to be pretty important to me when I was first really ‘getting into’ film back in the 1970s, and both of whom I had the privilege and pleasure to meet a few times.

As it happened, my first sightings of each man was when I was working at Portobello Road’s Electric Cinema Club in the late 70s; both lived locally and would come in very occasionally. (I also distinctly recall using the cinema’s stapler – ! – to temporarily mend the broken heel of a shoe worn by Theresa Russell, who was at that time living with Roeg.) By then I was, of course, familiar with each director’s work. I’d first seen Roeg’s Don’t Look Now (picture at top) during its opening run in my hometown of Northampton, checked out both Walkabout and The Man Who Fell to Earth while a student in Cambridge, and finally caught up with Performance at the Electric, where it was a late-show favourite – hardly surprising given the film’s Powys Square setting. As for Bertolucci’s work, I’d seen The Spider’s Stratagem during its run at the Academy and La Luna at (I think) the Notting Hill Coronet, while 1900 and Last Tango in Paris were both regular crowd-pullers at the Electric. (By the way, the only letter I ever wrote to Northampton’s evening paper was in protest at the local council’s banning of any screenings in the town of Last Tango – a letter which resulted in my being firmly rebuked in a sanctimonious epistle from a vicar who, like myself at that time, hadn’t seen the movie but who nevertheless insisted it would inevitably corrupt the morals of anyone who watched it.)

Later, in my capacity as editor of the film section of Time Out, I got to meet Roeg and Bertolucci properly, and over the years our paths crossed fairly frequently. Roeg I first spoke with when I visited him on the set of Heart of Darkness – not in sweltering Belize, but in cozy Richmond Green; he seemed to be expecting someone from Variety, not Time Out, which was an appropriately bizarre start to what proved, to me at any rate, to be a fairly confusing conversation. In interview, I found, Roeg’s thought processes seemed as fragmented, allusive, elliptical and elusive as the narrative structures of his films; happily, once one got off the subject of his creative methodology, things became clearer, as I discovered at several informal encounters in the ensuing years. A pleasingly wry sense of humour is what sticks in my mind.

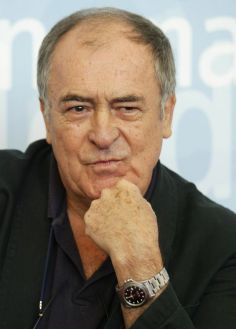

Bertolucci I had rather more to do with. My first proper encounter with him was at a party thrown by producer Jeremy Thomas for the release of Wim Wenders’ Wings of Desire;. Having been introduced to Bernardo by our mutual friend Tony Rayns, I then almost went and spoilt it all by spilling some red wine over the esteemed director’s short; fortunately, he realised that it was the fault of someone who’d bumped into me, and the conversation continued perfectly amiably. That, in fact, seemed fairly characteristic of his manner; certainly, in all my various dealings with him, whether professionally or informally, I found him warm, friendly, funny, charming and very readily talkative (particularly about movies). I was lucky enough to be invited on set for The Dreamers – for the sequence shot at the Louvre – and even luckier when he accepted my proposal that he write the foreword for a book I was editing. Needless to say, what he provided was an erudite and highly enthusiastic expression of cinephilia. Bernardo truly loved cinema, not just as a practitioner but as a spectator and thinker.

What one immediately notices when watching the films of Bertolucci and Roeg – and many would agree, I suppose, that in each case the most important and very greatest achievements came in the first half of the career* – is an utterly distinctive creative personality at work. These were men who were not only unafraid to make ‘personal’ films, but simply couldn’t make them any other way. As I’ve said, Roeg’s fractured, almost cubist storytelling style appears to have been a reflection of the way his mind worked, while Bertolucci’s films, oozing sensuous cinematic bravura, were inspired by his own thoughts and feelings about people, politics, relationships, the world… and, to no small degree, himself. Though he himself would speak of the influence of Godard on his early work, there is, perhaps, a comparison to be made with a rather different filmmaker, Ingmar Bergman, who also drew on his own dreams, desires, demons and doubts as material for his art.

Roeg and Bertolucci exemplify a particular approach to filmmaking that was perhaps at its most pervasive and powerful in the 60s and 70s: an approach which was about pushing boundaries of various kinds, and which believed in, depended upon and rewarded the intelligence, curiosity and adventurousness of cinemagoers. (Don’t get me wrong: there are still filmmakers around today who work that way, but the industry has changed, and not for the better as far as making movies of personal import and vision is concerned.) In short, Roeg and Bertolucci were artists, not simply technicians. That’s why they mattered, and why their films matter still.

* For the record my own five favourite Roeg films are (in chronological order) are Performance, Walkabout, Don’t Look Now, The Man Who Fell to Earth and Bad Timing. And my five favourite Bertolucci films (again in chronological order) are Before the Revolution, The Conformist, The Spider’s Stratagem, La Luna and Tragedy of a Ridiculous Man. But those favourites may change, of course…