One of the pleasures I derived last year from visiting the National Gallery’s ‘Radical Harmony’ exhibition devoted to the neo-impressionists was the opportunity it afforded to reassess the work of Georges Seurat. Though I’d been familiar (or so I thought…) with his experiments in pointillism since my teens, I had always found pictures like Bathers at Asnières and A Sunday Afternoon on the Island of La Grande Jatte rather underwhelming; the theory and practice of carefully assembling images from lots of different coloured dots was, for this layman, of little more than academic interest, while the human figures, for all their seemingly pleasurable lolling about on days off work, felt stiff, stilted, lifeless. What I discovered at the ‘Radical Harmony’ show was a quite different Seurat: in addition to some startlingly lovely drawings and the wittily playful Le Chahut – an intriguingly stylised depiction of can-can dancers – the show culminated in three ravishingly beautiful canvases painted in the northern port of Gravelines.

If you missed that National Gallery show, there’s now another chance to catch those three pictures – and rather more – at the Courtauld Gallery, in its exhibition ‘Seurat and the Sea’. During his all-too-brief lifetime (1859-1891), a substantial proportion of the inevitably limited number of works the artist produced were painted during five summer breaks on the northern French coast between 1885 and 1890 – some 26 of which are currently gathered together for the Courtauld’s show. Happily, human figures – still a weakness – are very few and far between in an exhibition that focuses on sea and sky, clouds and cliffs, ships, sails, and occasional buildings, bridges and bollards.

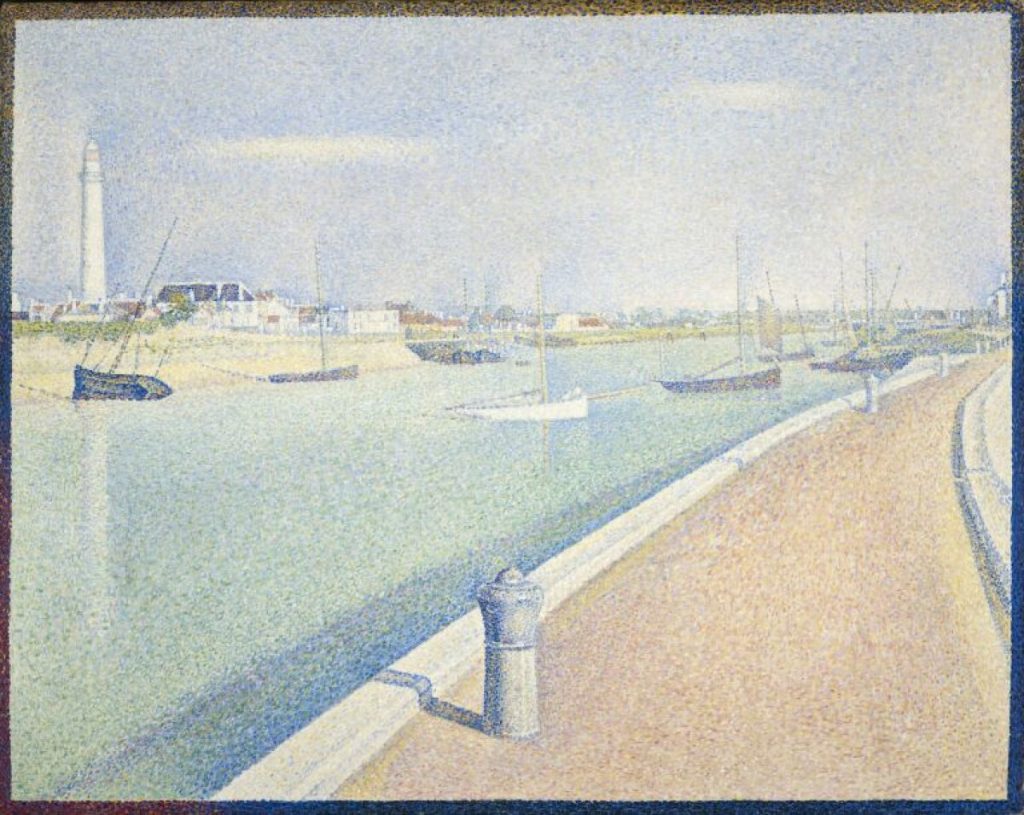

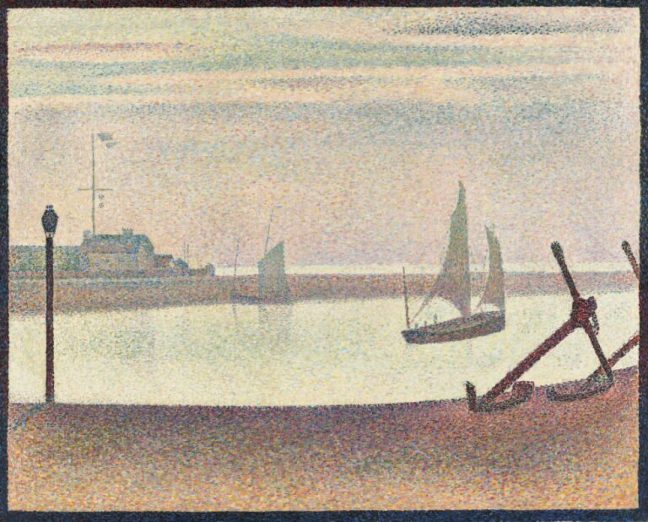

Enough with the alliteration. It’s one thing to wonder at Seurat’s boldly idiosyncratic pointillist technique by examining up close the juxtaposed marks of complementary colours; it’s another experience entirely to stand further back and simply submit to the works’ intense fascination with form and light. However faithfully Seurat depicted specific landscapes in locations like Gravelines, Honfleur, Le Crotoy and Port-en-Bassin – and a nice touch in the Courtauld’s display is the inclusion of several contemporary picture postcards enabling comparison of place and its representation – this is certainly not ‘realism’. The unemphatic but deeply rewarding concern with form even tends towards abstraction at times. A diagonal quayside or beach is perhaps even more a diagonal than it’s a quayside or beach (The Channel at Gravelines, Petit-Fort Philippe, 1890). A horizon becomes primarily a line dividing the distinctly still blue of the sea from the lighter and likewise unruffled blue of the sky (Beach at Bas Butin, Honfleur, 1886). A lighthouse or lamppost stands in strict vertical contrast to the level horizontality of land or water (The Lighthouse at Honfleur, 1886; The Channel at Gravelines, Evening, 1890 – picture at top). A tumbling slope of cliffs cuts the image in two, like diagonal split-screen (Seascape at Port-en-Bassin, Normandy, 1888). Then there is the light, be it luminous at the height of the day or richly burnished as evening falls. You can feel the painter’s profound immersion in these land- and seascapes; he wanted ‘to cleanse one’s eyes of the days spent in the studio and translate in the most faithful manner the bright light, in all its nuances.’ On the evidence of this lovely show – which also includes sketches and some quite stunning drawings (most notably, perhaps, Gravelines, An Evening, 1890) – he undoubtedly succeeded.*

Finally, a few words about ‘Lucian Freud: Drawing into Painting’, a new exhibition at the National Portrait Gallery which brings together 170 drawings, paintings and etchings. Opportunities to explore Freud’s work aren’t exactly rare, but this show does include rarely-seen drawings and studies, and there are rewarding juxtapositions with well-known paintings. One doesn’t need to go along with the view of the artist’s mother that the juvenilia to be found at the beginning of the show suggest a budding talent of note, and some of the notebooks and letters (‘I MISS YOU!) may fail to persuade you that Freud’s vision was, for all its coolly analytical observations, deeply empathetic. But there is wonderful artistry on view from the 1940s onwards, and one can even find a little tenderness here and there. If the self-portraits are as merciless as many of the others, there is surely great feeling of some sort in the pictures of his elderly mother, and, I suspect, a degree of respectful affection for David Hockney. As for the several pictures featuring whippets, whether dozing or just pretending, there is, for once, a very evident warmth.

Seurat and the Sea continues at the Courtauld Gallery, London, until 17 May. Lucian Freud: Drawing into Painting will run at the National Portrait Gallery until 4 May. Seurat images courtesy Courtauld Institute; Museum of Modern Art, New York; Indianapolis Museum of Art at Newfields; National Gallery of Art, Washington D.C. Freud’s David Hockney (2002) courtesy National Portrait Gallery, The Lucian Freud Archive, Bridgeman Images.

(* If I have not included a mention or reproduction of Seurat’s Le Bec du Hoc, Grandcamp, 1885 – indubitably a fine picture, and one of the best in the Courtauld exhibition – that is for two reasons. First, it has not been imported for the show, since it is held by the Tate. Second, as I explained to my art critic friend Sarah Kent, however great the work, I have a slight problem with it because – like most painters, including many of the greatest – Seurat simply couldn’t be bothered to paint birds in flight properly. Whatever the birds above the Bec du Hoc are meant to me – choughs, perhaps – they are depicted with an uncharacteristic laziness.)

I saw The Channel at Gravelines, Evening at a Pissaro show in the Ashmoleon in 2022 and thought it the best thing there, so can’t wait to visit this.

LikeLike