Until the recent release of a three-disc BluRay set on Criterion’s ‘Eclipse’ series, most of the films by the late, very great Iranian writer-director Abbas Kiarostami made before his 1986 breakthrough feature Where Is the Friend’s House? have been almost impossible to see, surfacing only at occasional retrospectives around the world. With the sole exception of his first full-length feature The Traveller (1974), I hadn’t seen them since 2005, when I programmed a complete retrospective at the National Film Theatre (now BFI Southbank) as part of a London-wide celebration of his films, photos, installations and verse. So the Criterion set Abbas Kiarostami: Early Shorts and Features, which includes 17 titles made between 1970 and 1989, all of which were digitally restored in 2018, is extremely welcome; the only films from that period now unavailable are Jahan Nama Palace (1977)– a documentary, commissioned by the Shah’s wife, about the restoration of one of the dynasty’s historic homes, which in my opinion is the most tediously conventional film Kiarostami made – and The Report (1977), a far more interesting dark drama about a civil servant undergoing both a marital and a professional crisis. Neither film was made for Kanoon (Iran’s Institute for the Intellectual Development of Children and Young Adults), the film department of which Kiarostami helped to set up, whereas all the films in the Criterion set – like Where Is the Friend’s House?, Close-up (1990) and And Life Goes On (1992) – were. Unsurprisingly, then, unlike his work from Close-up onwards, most of these early films are about children or young adults, even though very few of them could be said to be for that particular audience.

The 17 titles can be divided into three groups: shorts, fiction features and documentaries. Watching the shorts again after such a long gap, I was startled once more at how wonderfully strange they are. Bread and Alley (1970) and Breaktime (1972) are early examples of Kiarostami’s interest in journeys, not in the cars so familiar from the later features, but undertaken by boys on foot, returning respectively from a bakery (to be faced by a menacing dog) and from school (with the obstacle a perilously busy highway). As in Solution No 1 (1978), where a man stranded on a mountain road has to find a way to get back to his broken-down car, the journeys become tasks, challenges which must somehow be overcome by thought-through action; these films also display what would later be recognised as Kiarostami’s abiding interest in balancing drama and humour, activity and ‘dead moments’, and his gently experimental but subtly expressive approach to sound, repetition and point of view.

If Two Solutions for One Problem (1975) – his first film in colour – So Can I (1975) and Colors (1976), feel a little more didactic (though only the first, highlighting reconciliation as preferential in any conflict to revenge, would seem to have a clear ‘message’), they are all so unusual as to be beguiling, the first slapsticky, the other two verging on abstraction. Orderly or Disorderly (1981) is a small masterpiece; ostensibly a public information film designed to demonstrate, through contrasting vignettes of children then adults tackling various everyday problems, the superiority of methodical behaviour, it soon descends into (carefully choreographed) chaos, suggesting… well, who knows? Kiarostami’s is resolutely a cinema of questions and ambiguities; but as we hear his off-screen voice complaining that the filmed demonstrations are not working out as envisaged, we are left to ponder the relationship of film’s artifice to messy reality.

The Chorus (1982), his last short for Kanoon, again plays with sound while also showing that the director could create strikingly beautiful images, should he choose. That much had been clear from the three Kanoon fiction features (the first and third lasting only around an hour) made in the 70s. Experience (1973), about an impecunious teenager working at a photography shop whose crush on a middle-class girl might also, perhaps, lead to getting himself educated and away from his complaining boss, boasts memorably chiaroscuro compositions as well as sharp editing reminiscent of 60s New Wave movies. The Traveller (1974), about a still more impoverished and less self-disciplined boy determined to get to Tehran to see a soccer match, whatever it takes, is more reminiscent of neo-realism; with stark camerawork suggestive of both the protagonist’s single-minded obsession and his limited options, the film was the first of many masterpieces. A Wedding Suit (1976), was shot in colour, arguably more suited to the storyline, often quite comic despite its focus on three adolescents working in or near a tailor’s sweatshop, and surprisingly suspenseful in its final scenes (thus anticipating the steadily tautening structures of his later features). As in the shorts, the fundamental simplicity of the stories is offset by the imaginative invention evident in how they are narrated; we never know what will happen next. Moreover, and perhaps even more crucially, though most of the shorts and features, however funny or sad, are about young people, many of them leading far from comfortable lives that are unlikely to change much, cuteness and sentimentality are never for a moment allowed to intrude.

That’s true, too, of the documentaries, most in their different ways excellent, except for Tribute to the Teachers (77), an assignment from the Ministry of Education that feels almost as conventional and impersonal as the aforementioned chore about the Shah’s palace. While one can’t claim too much for Toothache (1980), an instructional film about the risks of not brushing teeth properly, it is engagingly lively, ingenious, and includes some delightfully amusing animation. But the other four are all worth seeing. First Case, Second Case (1979) is intriguing as an experiment made shortly after the overthrow of the Shah. Kiarostami shot a short film in which a schoolteacher decides to suspend seven teenagers from all lessons for a week because they won’t say which of them created a disturbance in class; the film is then screened to the boys’ parents and a range of officials and commentators, who offer their opinions on resistance, solidarity, informing, punishment and so on – issues entirely relevant not only to the Shah’s regime but to the Islamic Republic that replaced it. Kiarostami simply lets the people pontificate – there’s much moralising on display, from various viewpoints – and it’s chilling to bear in mind (as discussed in Kiarostami’s conversations with Godfrey Cheshire) that none of the authority figures remained in power; indeed, one was executed. As for the film, it was of course banned, not least because the women interviewed had not been wearing veils.

Any idea that after the Islamic Revolution, society in general (as opposed to opponents of the State) behaved in accordance with its laws was brilliantly undercut in Fellow Citizen (1983), in which Kiarostami’s camera simply records the excuses made by car drivers and passengers all fervently insisting they should be exceptions to a rule preventing vehicles entering the centre of Tehran in order to ease congestion. The extreme repetitiveness of the film is turned into a virtue, the brazenly selfish, sometimes outlandish claims of the seemingly endless procession of drivers and the patient response of the traffic controller becoming like a crazy ritualistic dance, both funny and compelling evidence that adults are generally far worse behaved than children and young adults.

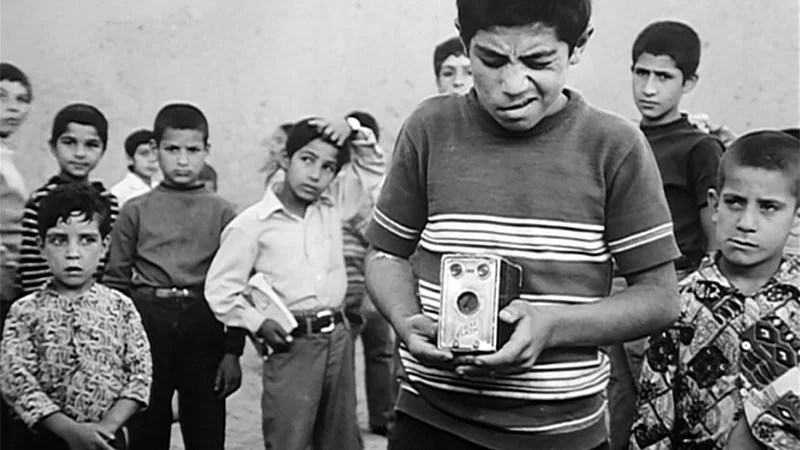

That much becomes all too clear in two films made in schools. First Graders (1984) also deploys a fair amount of repetition as it focuses primarily on sessions in which small boys visit the supervisor’s office to discuss the various misdemeanours they’ve been involved in: the ethics of forgiveness, punishment and broken promises are repeatedly explored in the teacher-pupils dialogues, to engrossing and illuminating effect, though it is clear that several sequences are staged, or at the very least re-enactments. Still better, and far more insightful and affecting is Homework (1989, pictured top) in which Kiarostami himself asks the similarly young boys about doing homework and what at home or at school might prevent them from doing it properly: illiterate or overworked parents, bullying siblings, and other factors come to light, just as the education system, with schools expecting families to provide tuition in subjects they’re unfamiliar with, is shown to be profoundly problematic. Damaging, too: most of the boys know all too what punishment is, but are hazy about rewards, and some seem traumatised by fear. Kiarostami this time acknowledges the effect he and his crew might be having on the young interviewees; the result is a film at once intellectually rigorous and heartrendingly moving.

There are moments in many of these early films which anticipate shots or scenes in the later, better-known works: a boy’s shadow moving across rocky ground in Breaktime, for example,will be echoed, almost 30 years later, by that of the protagonist in Taste of Cherry. More importantly, the Kanoon works – accompanied in the Criterion set by an informative essay by Ehsan Khoshbakht – not only see Kiarostami developing what would later be regarded as his highly distinctive skills as a cinematic storyteller, but looking at the world with both a keen, clear-eyed curiosity and a supremely humane compassion. They already reveal the creative presence of a master.

Abbas Kiarostami: Early Shorts and Features is released on BluRay by Criterion’s Eclipse Series, and is available at https://www.criterion.com/ Photos courtesy of MK2/Janus Films/Criterion, except the last, taken by Ane Roteta at the V&A in London, 2005