In early 2021, writing about Godfrey Cheshire’s book of interviews, Conversations with Kiarostami, I bemoaned the fact that there were so few decent books (in English, at least) about the late and very great Iranian filmmaker, photographer, poet and artist Abbas Kiarostami (1940-2016). Several years on, the situation has hardly changed, which is why I’m pleased that, around the same time as reviewing that volume, I decided to contribute to an Indiegogo campaign to facilitate the completion of another book by Cheshire, In the Time of Kiarostami: Writings on Iranian Cinema, again published by the Woodville Press. The book, it seems, first appeared back in 2022, but it’s only recently that I managed to get a copy and read it. Still, better late than never.

I’ve never met Cheshire, but he’s long been of interest to me since he was one of very few writers covering Kiarostami’s cinematic output when I was first becoming fascinated by it, around the middle of the 1990s. Kiarostami’s work, seemingly so simple in terms of story yet so subtle and rich in terms of resonance and ambiguity, can feel odd, even underwhelming at a first encounter, which is why it was useful to have Cheshire reminding us that it might be a little easier to grasp if one tried to watch the films in the order they were made; certainly, from Through the Olive Trees onwards, the later films are mostly more experimental, more audacious, more mysterious in various regards than the earlier ones (with the notable exception of Close-up, of course). Whereas Conversations with Kiarostami took us only up to 1999’s The Wind Will Carry Us, the new(-ish) book also covers most of the subsequent films, including 24 Frames, assembled and completed posthumously in 2017 by Kiarostami’s son Ahmad. The book also differs from its predecessor in that, instead of interviews, it largely consists of pieces devoted to film history, critical analysis and more personal reminiscence, some written specifically for the new publication, others taken from Cheshire’s extensive writing on the Iranian cinema from the early 1990s to the present.

As the full title suggests, the book is not exclusively about Kiarostami and his work; Cheshire also writes enthusiastically and informatively about films by Dariush Mehrjui, Mohsen and Samira Makhmalbaf, Bahman Ghobadi, Jafar Panahi, Asghar Farhadi and Mohammad Rasoulof, as well as providing a potted history of Iranian cinema. (One of the strengths of Cheshire’s understanding of Iranian film is that he is unusually well placed to examine it within the broader context of Iranian history, politics, art, literature and so on, having immersed himself in Iranian culture for some years.) But for me at least, the main focus is the book’s central section on Kiarostami, which includes important articles written for Film Comment (‘A Cinema of Questions’, 1996), Projections 8 (‘Seeking a Home’, 1998) and Cineaste (‘How to Read Kiarostami’, 2000), as well as new assessments of the later works and a personal tribute to a filmmaker who over the years became Cheshire’s friend. Since I too was privileged to get to know Kiarostami a little during the last 16 years of his life, I can confirm that Cheshire’s account of Kiarostami the human being seems to me as perceptive and unsentimentally appreciative as his grasp of Iranian culture is illuminating. (Incidentally, he also writes openly and intelligently about the dilemmas, advantages and potential pitfalls facing critics who become friends with filmmakers whose work they have championed.)

I concur especially with Cheshire’s descriptions of Kiarostami’s lightly-worn erudition, his warm, slightly mischievous wit and his constant curiosity, and with his assessment of the autobiographical elements in many of the Iranian’s films; like his friend Víctor Erice – they greatly admired each other’s work – he appeared to have no interest in making anything that didn’t mean something to him personally, which is surely why his films from And Life Goes On onwards feel so idiosyncratic, as if they were made not with any particular kind of audience or viewer in mind, but simply as a form of self-expression. (That’s one reason why, in my own book on his 2002 film 10, I wrote: ‘one can only suspect that – for want of a better phrase – Kiarostami may have been wanting to explore his own feminine side.’) As with Ingmar Bergman and, more recently, Nuri Bilge Ceylan, self-critique is an important aspect of Kiarostami’s work, even if it often manifests itself in characteristically oblique ways.

Cheshire’s take on Kiarostami’s work is consistently insightful, informed and thought-provoking. He is wholly right to say that having – presumably unintentionally – won over festivals and critics worldwide, ‘he turned to pleasing himself… his Experimental period was a return to his Kanoon period, when he could work playfully, idiosyncratically, without having to worry about big budgets or grandiose expectations.’ Cheshire’s take on the individual films that followed The Taste of Cherry is likewise illuminating. Admittedly, his exploration (in the aforementioned ‘How to Read Kiarostami’) of The Wind Will Carry Us with reference to certain strands of Persian mysticism and philosophy, for all its erudition, always struck this reader as perhaps a little too abstract, metaphorical, even quasi-structural to be fully persuasive, but that’s probably due to my lack of familiarity with the ideas he is discussing; moreover, there is much of interest in his reading of a highly allusive and elusive work. But his commentaries on both Certified Copy (taking in both Rossellini’s Voyage to Italy and Kiarostami’s own early feature The Report) and Like Someone in Love are typically appetising, again highlighting possible autobiographical impulses that might have fuelled the projects. Inevitably, any reading of 24 Frames has to be a little tentative, since we shall never know how Kiarostami himself would have finished the film. (Certainly, when Abbas showed me some of the material he’d made for it half-a-year before his death, he appeared to suggest that more of the vignettes based on paintings would make it into the completed assemblage. Whatever, Ahmad Kiarostami undoubtedly respected his father’s intentions as far as he was able, and the final results are both impressive and intriguing.)

Kiarostami’s body of work surely remains one of the most remarkable – and remarkably eccentric and original – in the history of filmmaking. While serving, admirably, to contextualise his many achievements through a wider understanding of Iranian culture, Cheshire’s book also recognises that Kiarostami was not just an extraordinary, very Iranian artist, but an extraordinary individual with, finally, a unique vision and a unique talent that render his work endlessly rewarding.

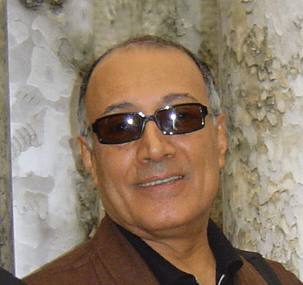

‘In the Time of Kiarostami: Writings on Iranian Cinema’ is published by Woodville Press and is available through Amazon or here: https://www.filmdeskbooks.com/shop/p/in-the-time-of-kiarostami-writings-on-iranian-cinema-by-godfrey-cheshire The photograph of Abbas Kiarostami, from the author’s collection, was taken in London in 2005 by Ane Roteta.