Less than a week ago, I learned that the filmmaker Terence Davies was seriously ill. This came as a shock; only a week previously had I led a discussion about Distant Voices, Still Lives with students at the London Film School. Seeing the film again had been a very pleasurable reminder of his particular cinematic genius; talking about it and its creator with the students (nearly all of whom greatly enjoyed the film, even though it depicts a world so different from the one they have known) reminded me of what fun he could be, and I thought to myself that I should get in touch with him and suggest we meet for drinks or dinner. Sadly, I had unwittingly left it too late; he was far more seriously ill than I realised, and now he is no longer with us. The news of his death came as an even greater shock, even though I had been warned his illness was such that he might not have long to live. It is hard, now, to credit that he is gone, that I won’t see him again, and indeed that there won’t be any more Terence Davies movies to look forward to.

Terence (though I’m still tempted to call him Terry, as I often have since we first met soon after his Trilogy was released in the early 1980s) was one of our very greatest filmmakers, and by ‘our’ I certainly don’t mean ‘British’; his finest work is extraordinary in all sorts of ways. His films were profoundly personal both in their content and themes and in their style. As with all great artists, his work was so distinctive as to be immediately recognisable as his. I’m not merely referring to the fact that his ‘autobiographical’ films – the Trilogy; Distant Voices, Still Lives; The Long Day Closes; and, later, Of Time and the City – were followed/complemented by works (several of them adaptations of other writers) which were still extremely pertinent to Terry’s own feelings about life, love, art, the world and himself. There is also his highly idiosyncratic approach to filmic narrative, dialogue, composition, camera movement, montage, music… everything, in fact, which is part of the art of cinema. Because he really did think of cinema as an art, not a business or a career, and it shows, in each and every frame he gave us.

I have written fairly extensively about Terence’s films, and I interviewed him many times over the years, for print, on stage, or on camera for releases of his films on disc. We never got to know each other that well but we certainly became good friends (I recall going to his 50th birthday do, and he came to at least four significant celebrations of my own). I didn’t manage a set-visit for The Neon Bible, but I did for The Long Day Closes and The House of Mirth; on the latter occasion, one of the producers asked me (as ‘family’) to try and talk Terry into returning to work after it had come to a sudden halt following a blazing argument with one of the cast; it took a while to get him back behind the camera (even then he insisted I sit beside him at the monitor while they finished filming the scene in question), but happily it worked out and the shoot was completed for one of his most emotionally devastating movies. He was a perfectionist, and always had a very precise idea of what he wanted; that could make him a fairly demanding director, but it also made for a great many remarkable achievements.

As others have pointed out, Terence had a wonderful sense of humour; notwithstanding his loneliness, his anger, his frustration, he was an extremely funny person, and was for the most part a joy to spend time with. He specialised in self-deprecation; my first ever encounter with him was over the phone, when he rang me at Time Out to thank me for my review of the Trilogy. ‘It’s such a wonderful review,’ said the rich, deep voice that would prove to be instantly recognisable over the years. ‘I’ve been committing it to memory. If I weren’t such an old misery, I’d be happy!’

I did very occasionally see Terence in darker moods, when his face could turn purple with anger, but mostly he was a delight, exuding an almost childlike pleasure in the knowledge that he was able to enchant and entertain others. He had, before he took up writing and directing, considered becoming an actor, and it was clear that he loved having an audience – to interview him on-stage was to witness a performance. He was expert in slipping suddenly but seamlessly from tragic to comic, and skilful in handling an audience (not to mention the interviewer). I hosted those events mainly on the stage of NFT1, at BFI Southbank, but the audience was no less charmed and amused by his antics at a masterclass at the Thessaloniki Film Festival (where a retrospective culminated in his receiving a special award). Yes, he knew from first-hand experience how cruel life can be, but when he was on good form – which was more often than not – his mischievous joyfulness was contagious.

I have many fond memories of times spent with Terry – I liked him enormously, and will miss him a great deal – but it was, of course, through his filmmaking that I first came to know him and admire him. In that regard, too, I have very vivid recollections. The premiere of Madonna and Child, the second part of the Trilogy, at the 1980 Edinburgh Film Festival, with its astonishing juxtaposition of shots of a Catholic church, choral music, and the sound of a telephone call to a tattooist about genital work. The press show of the completed Trilogy, with the closing Death and Transfiguration offering a boldly fragmented take on memory, suffering and release. A work-in-progress screening of Distant Voices, with the amazing cut from a rapt cinema audience – all smoke, tears and surging Hollywood score – to figures moving mysteriously through space away from the camera. The (in)famous ‘carpet shot’ in The Long Day Closes, a becalmed meditation on light, colour, time and place to the strains of Butterworth’s A Shropshire Lad. The closing scene of The House of Mirth, which left the members of a small preview audience speechless and in tears. A rough cut of Of Time and the City, watched at home on disc, the perfect matching of movement and music repeatedly making me feel thankful that Terence had at long last, after seven or eight years, been given funds to make a film again. The opening of The Deep Blue Sea, a beautifully fluent montage making eloquent use of Barber’s violin concerto. And, more recently, the unflinching, still starkly audacious studies of creativity and loneliness in A Quiet Passion and Benediction, with Cynthia Nixon and Peter Capaldi unforgettably depicting deep anguish. I could go on and on, since all the films are packed with moments of miraculous invention and expressiveness. But I won’t. Words cannot suffice for this man of cinema. Thankfully, though Terry is no longer with us, the superb films he gave us are. Watch them and marvel. And may he find the peace so often denied him in life.

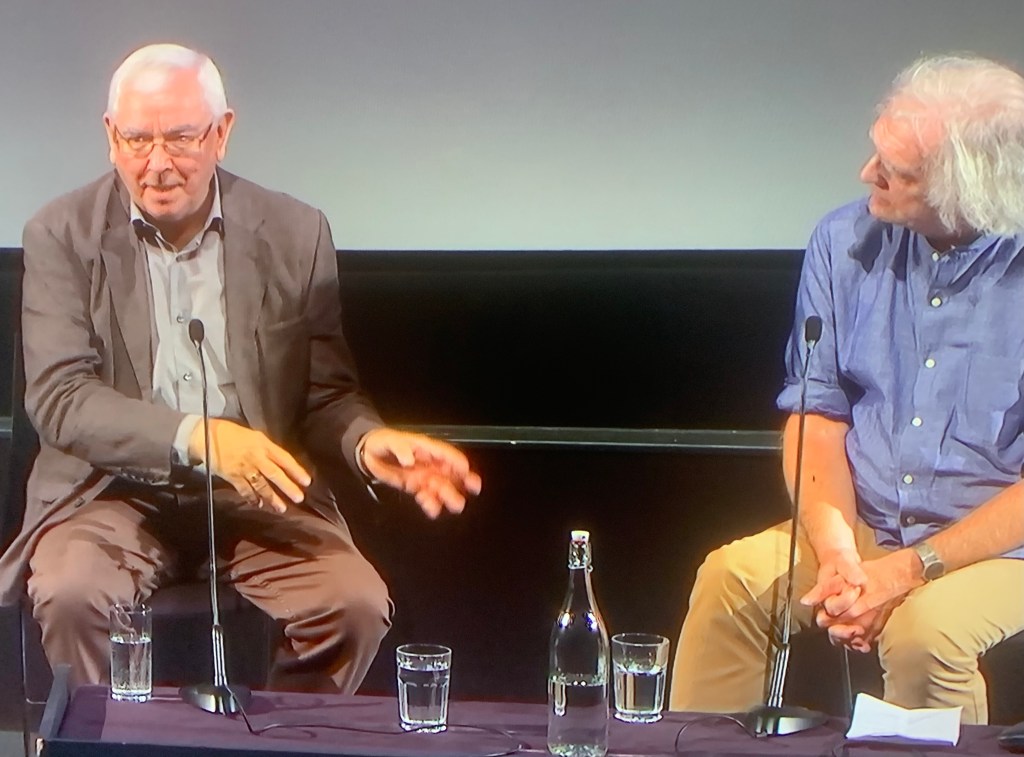

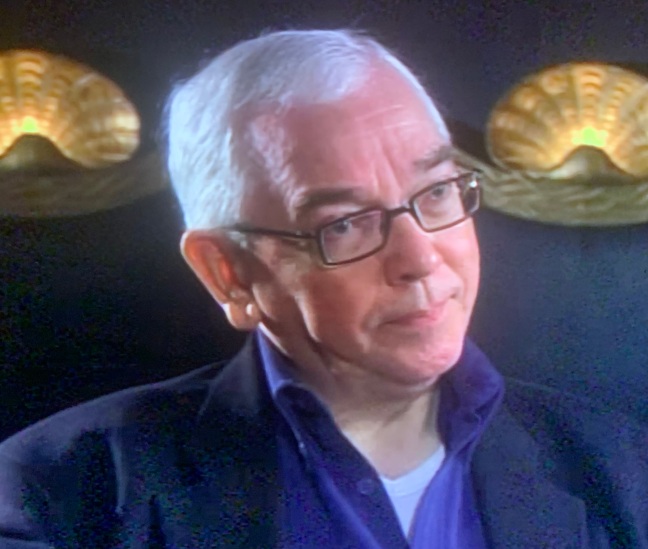

RIP Terence Davies (1945-2023). Images top and bottom from interviews conducted with the author for the BFI in 2008 (Rex Cinema, Berkhamstead) and 2018 (BFI Southbank).

Years ago, I painstakingly translated your book “film handbook” on my blog. I’m not sure if it was through it that I became aware of Terence Davies’ films. Although I haven’t seen all of his films, every one I did watch, even the less celebrated ones, I found something deeply moving in his work, and I was very saddened to hear of his passing two days ago. The last film I watched was “Benediction,” which also appears to be his final film, and I always held out hope for another Terence Davies film. I personally find his approach, especially concerning gay/queer themes, more robust than that of his then-contemporary Derek Jarman, who had a more militant/vanguard stance. I have the impression that his films will withstand the test of time more gracefully. Rest in peace, Terence Davies.

LikeLike