For me at least, there could be few BluRay releases more welcome than a new boxed set of four classic crime serials by Louis Feuillade. ‘Louis who?’ you may be wondering, and not without reason, even if the French filmmaker was enormously successful back in the 1910s, i.e. in the years when the cinema was moving from shorts to features and beginning to develop much of the style and syntax we know today. Indeed, it’s arguable that Feuillade (1873-1925) was just as important as DW Griffith in advancing the art of cinematic storytelling – and, moreover, that his films feel a great deal more modern (and, probably, more consistently enjoyable) than those of the American pioneer.

So why isn’t Feuillade better known? Well, had he lived long enough to continue working in the sound era, things might have been different. But mainly, his comparative obscurity is as so often due to the availability, or rather the invisibility, of his films. (I’d only managed to see two of the serials before this new release.) For some years after Feuillade’s heyday, he was dismissed by some as a populist entertainer limited by his adherence to a lowly, even disreputable genre; by the time of his early death at the age of 52, ’serious’ film folk tended to favour the more emphatically arty fare of Griffith, the German expressionists, the Soviet montage-theorists, and Feuillade’s more self-consciously experimental compatriots like Marcel L’Herbier and Abel Gance. The once hugely important Feuillade – he’d not only directed around 800 films (many of them shorts, of course) but as artistic director at Gaumont oversaw the studio’s entire output – was widely forgotten until Henri Langlois, co-founder of the Cinemathèque Française, unearthed and screened some of the great serials in the 1940s and 50s. A rediscovery of sorts had begun, and Feuillade came to be recognised as one of the very greatest – and most influential – artists of cinema’s early years. The trouble was, the serials for which he is rightly acclaimed are not short – the many episodes for each one usually add up to a total of between five and severn hours – so they’ve sadly not been screened as frequently as they deserve.

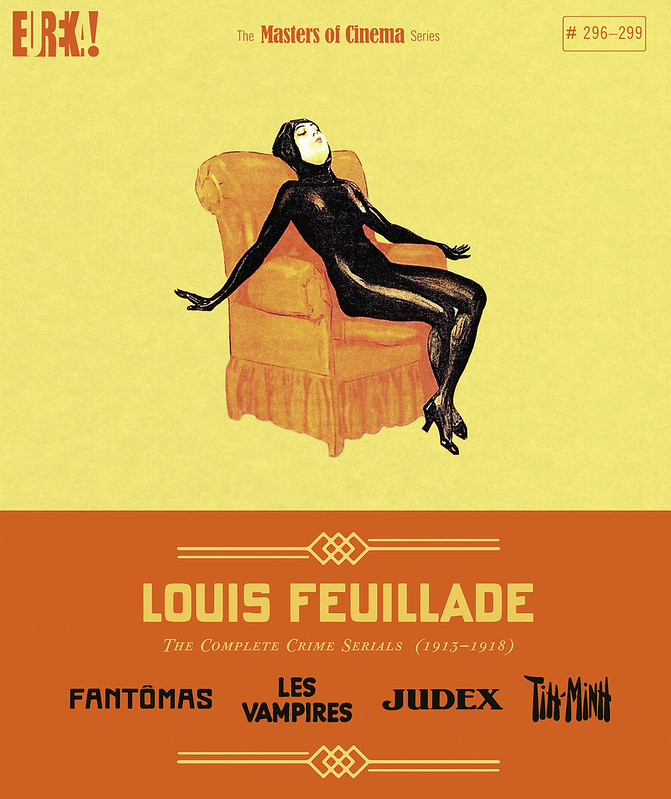

Which is why Eureka’s nine-disc set ‘Louis Feuillade: The Complete Crime Serials (1913-1918)’ is such a boon, including as it does beautifully restored versions of Fantômas (1913-14), Les Vampires (1915-16), Judex (1916) and Tih Minh (1918) (To be fair, the set’s title is misleading, because La Nouvelle Mission de Judex (1917) is not included; that said, it’s reputedly a less impressive piece of work, so perhaps it’s no great loss for now.) To some extent, the four episodic serials in the box all have fairly similar storylines featuring Establlshment figures battling against mysterious, anarchic criminal gangs; each has its share of secret passages, hideaways and codes, chloroform kidnappings, miraculous escapes, sudden surprise reversals and improbable coincidences, not to mention many meaningfully furtive glances and copiously abundant facial hair, disguise being a tool much deployed by dastardly villains and determined heroes and heroines alike. However, these and other generic conventions notwithstanding, there is considerably variety, not to mention creative progress, in the four works, such are Feuillade’s fecundity of invention and the care, commitment and evident joy he took in depicting a universe at once familiar and fantastic.

In Fantômas – based on a pulp best-seller (the other three are all originals) – Inspector Juve and his young journalist friend engage in an extended battle of wits with the titular jewel thief, a master of disguise who’ll stop at nothing, however murderous, to have his sadistic way. In Les Vampires a journalist and his bumbling sidekick are pitted against an underworld gang led by fiendishly cunning masterminds, including the famously seductive Irma Vep (played by the justly acclaimed Musidora, and pictured at top). Judex is the nom-de-plume for the vengeful son of a man ruined by a ruthlessly corrupt banker, whose crusading cause brings him and his brother into conflict with a couple of serial kidnappers (one of them brilliantly brought to life by the aforementioned Musidora). And in Tin Minh, an explorer, his family, friends, servants and eponymous fiancée are forever being threatened by a colourfully protean trio of villains who are seemingly out to get hold of some occult Oriental treasure but actually pursuing far more sinister aims.

It would be all too easy to dismiss all this as absurd hokum, yet Feuillade manages, against the odds, to make his often outlandish storylines not only compelling but even, within the fantastic and mostly melodramatic terms of the world on display, strangely credible: amazingly, we are somehow made to suspend disbelief. He succeeds thanks to his utterly distinctive commingling of the real and the unlikely. With the notable exception of some comic mugging by Marcel Lévesque (whom you may recognise from Renoir’s later Le Crime de Monsieur Lange) as a sidekick in Les Vampires and Judex, most of the performances are admirably naturalistic, just as the world they inhabit – both the interiors shot on realistic sets, and the many exteriors shot on location – faithfully reflected that inhabited by the films’ first audiences; the shots on the streets of Paris and Nice retain an almost documentary-like fascination today. The characters, too, are for the most part recognisably human, for all their tendency towards hirsute disguise. The women, especially, are worlds away from Griffith’s virginal waifs and matrons; they’re admirably intelligent, courageous, down-to-earth, unflappable and, particularly in the case of Musidora’s Irma Vep and Diana Monti, undeniably and unashamedly sexual. As played by René Cresté, Judex, it’s true, seems to have few distinguishing characteristics other than filial duty, a commanding noble profile and a flamboyant way with a cape, but at least he’s not really a ‘superhero’, despite his expertise with hounds and menacing letters; furthermore, by the time the actor gets to play the explorer d’Athys in Tih Minh, he’s able to suggest a more fully rounded character.

So a kind of realism is in play throughout, even as the stories invoke ubiquitous conspiracy, masterly criminal cunning, and the downfall of society as we know it – or, as my late friend, the writer Gilbert Adair, put it with characteristic insight, ‘the Paris of that curious transitional period, half nineteenth, half twentieth century, half fin and half début de siecle, which the Eiffel Tower appropriately bestrode’; rest assured we do get to see that iconic monument at one point in these series, but mercifully not too often. (Strangely, though they were made just before and during the First World War, that conflict is never mentioned, and any idea of Germany as an enemy only occurs as late as halfway through Tih Minh.) These are films set in a familiar everyday world – a world notable for its still fairly recent technological developments: cars, telephones, microphones, electrical gadgets, surveillance cameras! – albeit one where very little is in fact as it initially seems. Appearance is not the same as reality. Identity is fluid, memory unreliable – or simply gone. Order is constantly at risk of sliding into chaos. The stuff of dream, especially of nightmare, is invariably just around the next corner. Perhaps that, too, is one reason why the films still feel so modern. It’s certainly why Feuillade has been seen as a precursor of Lang (especially The Spiders and the Mabuse films), and most especially of Hitchcock. (Other admirers who seem to have absorbed his influence are Georges Franju, Alain Resnais and Olivier Assayas, though I suspect there have been many more.)

The predominant aura of realism is enhanced by Feuillade’s use of long takes and meticulous, mostly static in-depth compositions; both suggest the veracity of what we are seeing, and ensure that some of the vertiginous stuntwork we see on buildings and steep hillsides is genuinely breathtaking. (My vertigo kicked off fairly often as I watched the four films.) It’s helpful, I think, to try to watch the serials in the order they were made; you feel Feuillade becoming ever bolder in his cinematography, introducing larger groups of people (always carefully blocked), more complex compositions, more dynamic and eloquent camera movements, more flashbacks, more visual coups, and so on. A key development was his move from Paris to Nice, where he could make use not only of the Victorine Studios but of the mountains and perched villages high above the city. The last few episodes of Tih Minh are especially exhilarating; it is also, I’d suggest, the most visually beautiful of the films, though all four are notable for their precision, elegance and expressiveness.

(A brief note about the music on these discs. Judex alone has a piano soundtrack specifically composed and improvised (by Patrick Laviosa) for the movie; inevitably it is therefore less uneven than the compilations assembled for the other three (of which Tih Minh’s is the most satisfying), but it is also more repetitive in its repeated return to the ‘Judex’ theme. All the soundtracks have their strengths and shortcomings, but so vivid are Feuillade’s images, so engrossing his storytelling, that any weaknesses soon become negligible.)

In short, the Eureka set, with its glorious 4K restorations – not to mention a few impressive extras – offers a marvellous chance to discover four cinematic treasures from a major filmmaker too often neglected. They are exciting, mysterious, sinister, surreal, chilling, witty, tender, sexy, funny, innocent, sophisticated, timely… and ceaselessly imaginative and entertaining. Here are a few apposite words from David Thomson’s ‘Biographical Dictionary of Film’.

‘Feuillade [is] the first director for whom no historical allowances have to be made. See him today and you still wonder what will happen next… Feuillade predicts a twentieth-century world yet to come. Even in the years of the First World War, he looked past the horrific clash of machines guns and cavalry, of mud and dress uniform, to an atmosphere of urban anxiety… Not only had Feuillade’s pregnant view of grey streets become an accepted normality; his expectation of conspiracy, violence, and disaster spring at us every day.’

Thanks be to Eureka and Gaumont. I have just one request of them. When can we see Feuillade’s later and likewise acclaimed Barrabas?

‘Louis Feuillade: The Complete Crime Serials (1913-1918)’ is released in a limited edition by Eureka as part of its The Masters of Cinema Series. The trailer is here.