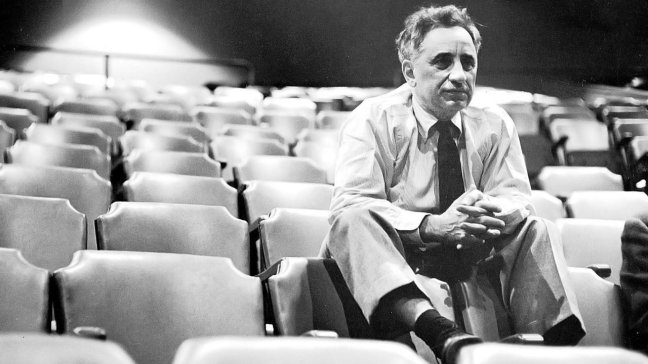

When my colleagues in the programming team at BFI Southbank decided to take up my suggestion that we should mount a retrospective of the films of Elia Kazan – the last one had been way back in the early 1970s – I thought it would be interesting to curate it myself and even, perhaps, to give an illustrated talk by way of an introduction to the season. I wanted to do that because the acts of researching the retrospective and preparing the talk offered me an opportunity to re-consider his achievements as a filmmaker. I always embark on the work required for such talks in a spirit of curiosity – it’s a chance to immerse myself in a body of work and think about it in more depth – but in the case of Kazan there was another factor involved: I had a sneaking suspicion that, many years ago, I might not have been sufficiently appreciative of his achievements. I wanted to see if that suspicion was correct.

In 1989 I had been commissioned to write ‘The Film Handbook’, a critical dictionary of 200 or more directors; the publishers wanted someone famous to provide an introduction, and as a long shot I asked Martin Scorsese, whom I’d met a couple of times, to do so. Much to my surprise and delight, he agreed, and was sent the manuscript. I’ve no idea how much of it he read, but at the very least he evidently checked out what I’d written about some of his favourite directors. His response was gratifyingly enthusiastic, though he did feel the need, in passing, to advise: ‘Very often I agree with Geoff Andrew; sometimes not. I certainly don’t agree with his entries on David Lean and Elia Kazan, who both made films of the greatest importance to me.’

Well, yes; perhaps I had been a little harsh. While praising Kazan as an actors’ director, I had also claimed that, ‘His work… is variable, veering from low-key realism to hysterical melodrama.’ I’d described him as ‘a director of memorable scenes rather than fully realised films: the cost of focussing on performance at the expense of everything else.’ After writing those words, I would occasionally revisit one of Kazan’s films, and sometimes I’d have second thoughts. But preparing for the BFI’s current retrospective afforded me an opportunity to examine whether I had got things wrong all those years ago and, if so, to ask myself why.

With the benefit of hindsight, I do now feel I had been too harsh. Kazan’s work was undoubtedly ‘variable’ – that’s not at all unusual – but I had underestimated his achievements. Was that because I knew he had ‘named names’ at the House Un-American Activities Committee hearings, helping to ruin the careers of several colleagues? I don’t think so. That may have explained his enduring unpopularity in some quarters, but I myself have long felt it is crucial to distinguish very clearly between an artist’s life and their work. In my case, looking back I feel there were probably other reasons why I didn’t really give Kazan his due back in the 1980s.

First, and most obviously, there was the question of his work’s availability. Before the advent of DVD and online streaming, it was harder to see many of his films. The most famous titles might turn up at the repertory cinemas or on BBC2 or Channel 4, but if you wanted to catch the lesser-known movies you had to keep an eye on the TV schedules and on the rare occasions when they were programmed – usually in the small hours or when one was at work – you had to remember to set the video to record them. The early films were particularly hard to see, and a few of them turned out to be considerably more rewarding than the ‘minor apprentice works’ they were characterised as by some writers.

Second, there was my own personal taste at the time. Back in the 80s, if memory serves, I probably had rather silly ideas about what was ‘cinematic’, what was ‘televisual’ and what was ‘theatrical’. I’m sure I probably felt at that time that Kazan was excessively ‘theatrical’. What’s more, I recall comparing his films unfavourably with those of his friend and erstwhile colleague Nicholas Ray, whose work I adored so much that I devoted my next book to it. It was a needless, in many ways pointless comparison, but all critics make their mistakes, and this was one of mine. Overall, I still tend to like Ray’s films more than Kazan’s, but that certainly doesn’t mean that the latter’s weren’t ‘cinematic’, let alone that they weren’t good, groundbreaking, or even great. And I readily admit (and would have done so in the 80s) that Kazan enjoyed more critical and commercial success than Ray – or indeed most other American filmmakers working in the postwar years. Furthermore, Kazan’s influence on actors and acting remains immeasurable.

Re-considering Kazan wasn’t, perhaps, as straightforward as I’d hoped. He appears to have been a man of many uncomfortable contradictions, and that may be reflected in his work. Even now, many of his films just won’t settle down easily in my mind; they’re full of intriguing, unexpected details and they can raise strange questions that aren’t easily answered. What I do know is that he was a considerably better filmmaker than I once believed; Scorsese was right to take issue with me on that.

If you’ve read this far (and if you have, thanks for doing so!), you’re probably wondering which of Elia Kazan’s films I rate most highly. So here below, very roughly in order of preference, are my ten favourites (though note that I have yet to see The Visitors).

Wild River, 1960, with Montgomery Clift, Lee Remick, Jo Van Fleet, Jay C Flippen, Frank Overton

America, America, 1963, with Stathis Giallelis, Frank Woolf, Linda Marsh, Lou Antonio, Paul Mann

East of Eden, 1955, with James Dean, Julie Harris, Raymond Massey, Jo Van Fleet, Richard Davalos

Panic in the Streets, 1950, with Richard Widmark, Paul Douglas, Jack Palance, Zero Mostel, Barbara Bel Geddes

On the Waterfront, 1954, with Marlon Brando, Eva Marie Saint, Rod Steiger, Lee J Cobb, Karl Malden

A Streetcar Named Desire, 1951, with Marlon Brando, Vivien Leigh, Kim Hunter, Karl Malden

A Tree Grows in Brooklyn, 1945, with Peggy Anne Garner, Dorothy McGuire, Joan Blondell, James Dunn, Lloyd Nolan

Splendor in the Grass, 1961, with Natalie Wood, Warren Beatty, Pat Hingle, Barbara Loden, Audrey Christie

Baby Doll, 1956, with Carroll Baker, Karl Malden, Eli Wallach, Mildred Dunnock

Man on a Tightrope, 1953, with Frederic March, Terry Moore, Gloria Grahame, Adolphe Menjou, Cameron Mitchell

The retrospective ‘Elia Kazan: The Actors’ Director’ continues at BFI Southbank until 15 March 2020. Of the early films which have screened already, both A Tree Grows in Brooklyn and Boomerang! are available (as is Wild River) on BluRay and DVD on Eureka’s Masters of Cinema series.

Very nice piece, Geoff, and honest. Baby Doll is probably difficult nowadays, but I admired it more than Lolita when I first encountered them. Props to Scorsese too for expressing his own reservations while still doing the introduction. The way discourse should work.

LikeLike

Kazan is a hard personality to separate from his persona as an “actor’s director” and as a film director. His films tend to have great, actor moments but lack a real director’s eye for visuals that tell their story independent of performances. Also, were you ever bugged by the offputting voice-overs in East Of Eden? Like the laugh of the black prostitute directed towards Cal at the beginning of the film as he hovers outside his mother’s house of ill repute? And the silly performance of her henchman, Timothy Carey?

LikeLike

I used to regard him primarily as an ‘actor’s director’ but when I was revisiting the films in the order he made them by way of research for the NFI season, I found that many of them were actually far more repressively directed – in terms of composition, pacing, camera movement, colour, editing, etc – than I had realised. In general I found that I liked and admired his work rather more than I had expected. I was never bothered by any of those things you mention in East of Eden – yes, Timothy Carey always tended towards the excessive, but that is surely one of the joys of watching him for his admirers (of which, I think, I am probably one, since he was such a distinctive cinematic presence).

LikeLike